Economics | 12 February 2019

It sounds like a story from the heady days leading up to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and something that will end in disaster. Rating agencies assigning the highest possible rating to an auto maker’s debt which is ‘guaranteed’ on clients paying for leases of its cars (which is essentially debt), with repayment on the final amount expected to come from car sales when leases come due.

However this is exactly the case with the senior tranches of Tesla’s most recent debt issuance, where the company raised $837mln in December, having raised $546mln last February. This is the same Tesla that until the middle of last year had been cash flow negative for every quarter but one since inception, and who was struggling to deliver on orders it had already taken payment for.

It is actually a fairly common way for car companies to issue debt in order to reduce coupon payments, with the securities issued by a special entity aimed at protecting investors in the event of a bankruptcy by the manufacturer. Investors are actually taking more of a bet on a company’s (hopefully highly credit-worthy) customers than the company itself, and that the cars remain popular and serviceable even if Tesla were to go out of business.

However these guarantees doesn’t necessarily make the debt that safe. Although contractually obliged to keep up lease repayments, it is easy to see it being reneged on if customers get into financial difficulty. After all, most people would rather eat and pay off their mortgage than pay monthly financing on their cars. Further the market for used electric cars is not well established. That said, you would expect anybody buying a Tesla to be pretty well off and almost immune to such considerations, but at the moment economic growth in the US remains quite good; if/when thing turn you always find instances of people who stretched themselves too far, and probably few buyers of a luxury second hand electric car.

Something that is very hard to measure quantitatively but which we are hearing more and more is that there has been a backlash in the last year against bonds coming to market with weak covenants, which place restrictions on the borrower, for example restricting the amount of further debt the borrower can take on. However the example of Tesla doesn’t, to me, indicate a market being overly demanding of borrowers.

Should we trust ratings from credit agencies? Mostly. Despite accusations that they had been overly generous with ratings prior to the Global Financial Crisis, it was only in the collateralized debt sector where there seems to have been a major misunderstanding of risk, while defaults on regular company debt were within the bounds of expectations. CDOs, CMOs and CLOs (the securities in the collateralized debt sector) are a step up in complexity from regular ABSs (asset backed securities), the category into which auto-lease bonds fall.

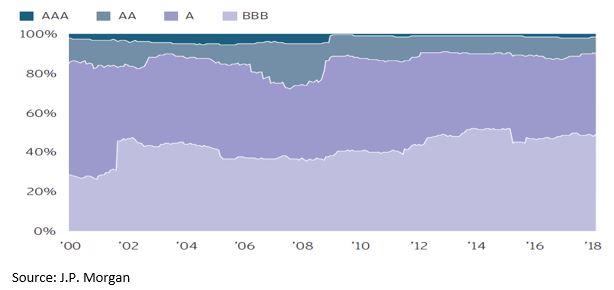

Further, whether it has been that credit quality has been falling, or that rating agencies are being more discerning, companies are achieving lower ratings on average. Looking at US issues, pre-2007 about 40% of companies had a rating of A and 33% BBB. Today more than 50% have a rating of BBB and only about 25% have an A rating.

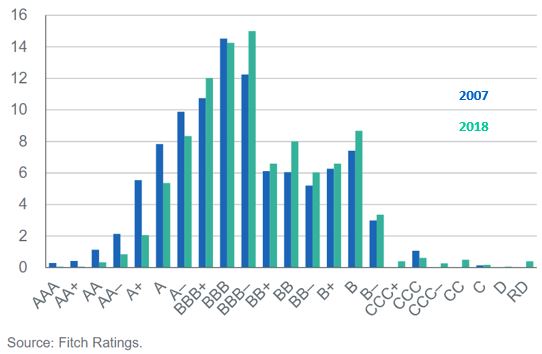

However the high proportion of debt hanging onto investment grade status (BBB-) in the more granular chart below, which also includes high yield, implies perhaps an unconscious reluctance to downgrade debt below investment grade.

The implication for investors is that investment grade funds, especially those which track an index, may not be as safe as you would think. We would argue that, especially in the fixed income space, an active manager’s ability to make an independent assessment, and so be sure that an AAA rated auto-lease bond from Tesla is in fact extremely safe and attractive on a risk/return basis, is a distinct advantage over passive investing.

Comments