You can relax. The Fed has no intention to fight inflation (yet).

You can relax. The Fed has no intention to fight inflation (yet).

You can relax. The Fed is (probably) not serious about fighting inflation.

When the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre embarked on an all-out war against the monarchy in 18th century France, he probably feared that his end would come at the hands of the Royal Executioner. But the French king was beheaded first. Then he feared that the Aristocrats would take revenge. But their heads also fell before his. Still, he saw enemies everywhere. As a result, nearly 300,000 were arrested and at least 30,000 lost their lives during his ‘Reign of Terror’.

In the end, what brought Robespierre before Charles-Henry Sanson, the High Executioner of the First French Republic (ironically previously the Royal Executioner), was the one enemy that could not be intimidated: inflation.

As the monarchy collapsed under the weight of failed economic policies, the new French government printed money called the ‘Assignat’. The greater the needs of the new bureaucracy trying to control a country in anarchy, the more money was printed. Between 1789 and 1794, the new currency had collapsed to 1% of its original value. The prices of goods and services soared, resulting in large-scale hoarding. People that were hungry under Louis XVI, grew even hungrier during the revolution. The government attempted to curb wage inflation. On 23 July 1794 the Commune limited the wages of employees, in some cases by half, provoking sharp protests and strikes across all of Paris. Five days later Robespierre was arrested and his own head promptly rolled in the Place de la Revolution, less than a thousand days after those of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Inflation is a primary enemy of stability. Even at its most benign, it can become a very visible proof of policy failures. At its worst, it can equally topple the most brutal despots or the most stable democratic governments. It is no coincidence that the number one mandate of all central banks across the globe is price stability.

The current inflation

Except for the 2011-2012 Euro crisis, the Fed, the world’s de facto central bank, has not seen persistently high inflation in the past twenty years, a gift of China and globalisation. However, prices in western economies have been rising dramatically in the past few months, a confluence of pent-up demand, broad inefficiencies across a global supply chain gasping to re-stock and wage pressures from a workforce in disarray. US inflation tops 5% for the last three months. In the UK it is about half that, but it is still above the BoE’s threshold, and it could go higher.

In normal times, investors would have been modestly worried about such an inflationary event. Equities tend to underperform versus average when inflation hits and bonds lose value in terms of real (post-inflation) returns. This time around, the threat is much bigger. What is at stake is the way we have been investing for a decade.

Since 2008 asset returns have been consistently underpinned by the willingness of central banks to suppress risk by buying assets. Four attempts to stop ‘Quantitative Easing’ have resulted in market and economic stagnation. One strategy to reduce central bank balance sheets collapsed five months before Covid-19 became an issue. The cornerstone of the so-called ‘only game in town’, central bank accommodation, was low inflation. As long as prices remained in check, money printed by central banks was ‘real wealth’, circulated in the financial economy and inflating only the prices of stocks and bonds, not those of food and iPhones. Prices on the shelves remained relatively steady, but assets in pension investment accounts nearly doubled in the past decade. Hardly a cause for revolution.

The more inflation rises, the more the current monetary-driven regime is in danger. “Can the Fed continue to print money”, portfolio managers wonder, “when prices on the shelves rise at the current pace?”

Unconfusing the inflation debate

A big problem is that the inflation debate is confused. Interest rate hikes are often seen as a panacea for all price problems. However, this is simply not the case.

Inflation can be caused by high demand for goods, or limited supply, or both. Interest rate hikes and the cessation of Quantitative Easing are tools primarily designed to curb demand-side inflation. The central bank would raise interest rates to curb excess lending, which leads to higher demand and ultimately would cause a rise in the prices of products and services.

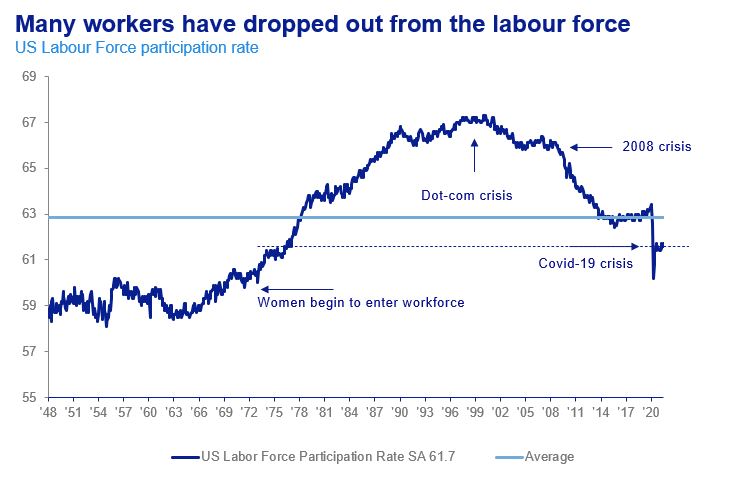

Is there evidence of demand-side inflation? Yes, but it is limited. Post-lockdown pent-up demand is petering out. In the US, the ‘labour participation rate of the economy’ (the proportion of the working-age population who are either employed or looking for a job) fell from 63.5% to 61.2% during the pandemic. The situation is similar across the world. This fall was enough for labour shortages to occur and push prices up. Prominent economists like Larry Summers are worried that these pressures will persist. However, central banks consider this drop transitory and expect labour supply to increase once Covid-19 childcare issues can be addressed.

Conversely, more convincing evidence points toward supply-side inflation. Energy costs are up 23% for the year. Dry cargo prices are at cycle highs and container rates are at all-time highs. Factory delivery times have not been as long in more than a decade. The Delta variant is making things worse for supply than demand. Western consumers are mostly vaccinated and have less fear of generalised lockdowns. Thus, demand is on its way to be streamlined. Vaccination rates for the developing world are still meagre. Only 20% have received both doses of a vaccine required to stave off Covid-related hospitalisation. The developing markets are home to 6bn people and the starting point of many supply chains.

The Fed has little incentive to hike rates

With inflation pressures coming mostly from the supply side, there is little the Fed can do to curb it. Interest rates are tools best used to cool down the economy during a mature, credit-driven economic boom. They are not designed for a recovering economy and much less for one still under the threat of a pandemic. Interest rate hikes could curb some excess demand, but they risk dampening consumers’ newfound optimism with very little to show for it. They would not fix supply issues, closed borders, lockdowns in emerging markets, delays in production, energy and transportation costs etc.

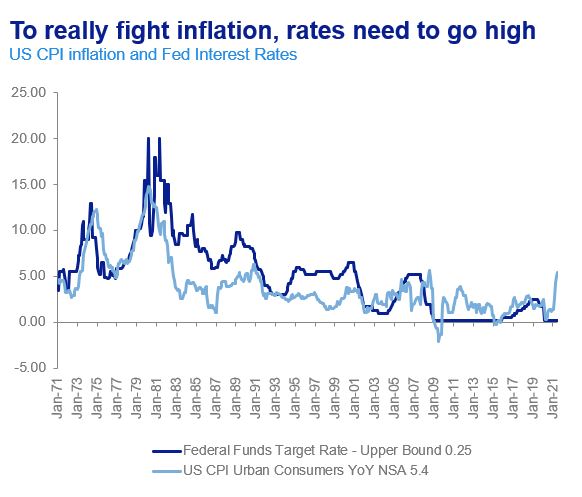

We believe the Fed knows this. We also believe that if it was serious about fighting inflation, the FOMC, the Fed’s rate-setting body, would not be forecasting minimal rate hikes in eighteen months, or some moderate tapering of quantitative easing by the end of 2021. To fight inflation, historically, one needs interest rates higher than the CPI. For a 5% CPI, the Fed would need at least 6% rates, now, not 0.75% in two years. Thus, they are willing to treat the present inflation factors as transitory, and they are willing to wait.

Even if this inflation bout lasts longer than expected, the Fed might welcome a modicum of inflation anyway to reduce the global debt burden, currently at an unsustainable 356% of annual global GDP. On the other hand, raising rates could risk indebted entities, many of which are national governments and consumer wellbeing.

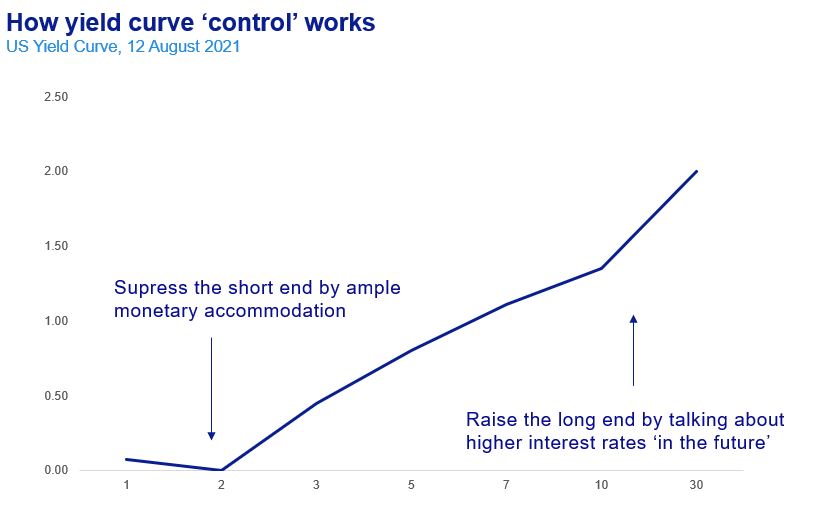

A salient point for investors is that, whereas the Fed probably has no intention to fight inflation, it might take advantage of high inflation to ‘talk’ future rates up. By extending the short-term supply of money and ‘threatening’ rate hikes in the future, it can try to manipulate the long end of the yield curve higher, which helps the bond market stay alive and provides an incentive for banks to continue lending. It is also covering its bases in case it does need to push through fast rate hikes if demand-inflation occurs as a result of Mr. Biden’s fiscal stimulus package.

What this means for investors and our portfolios

For one, we would follow the decree of ‘looking at what the Fed does, not what it says’. Market consensus is also pursuing this strategy which is why bonds and equities have barely reacted to recent hawkish comments from the FOMC. We may even consider any surprise rate hike as a possible ‘policy error’.

It also means that we are less fearful of a rate-driven bond rerating in our portfolios. Markets may well decide by themselves that bonds are too expensive, especially in light of persisting inflation, and thrust long rate rises. But we don’t expect policymakers to go anywhere near this particular bubble. We have already been underweight bonds in our portfolios and are actively looking into ways we can further decrease risk, especially for the more conservative portfolios.

Ding-a-ling. Financial Santa is in the house, but does he also bring rate cuts?

Unlike the real Santa, who brings his gifts late in the year, the Financial Santa, tends to begin a couple of months earlier.

Don’t write off 2023 just yet

After 2022, the annus horribilis, it was widely assumed that 2023 would be a rebound year. However, up to the end of October, a 60/40 (MSCI World/Bloomberg Barclays Global Bond Index), was up a mere 2%, very far from the average uplift of 5% and 9% experienced in a rebound year.

No end in sight

Last Friday, UK GDP came in a tick higher than expected. In this case, a 0.2% surprise is by no means insignificant. The fact that the economy was able to eke out growth in the face of already aggressive interest rate hikes will galvanise the Bank of England’s zeal to continue tightening monetary policy.

Know when to take risks, and when not to

‘Providence protect idiots’ Otto Von Bismarck once exclaimed. I’m never quite sure what the direct intentions of the Almighty are. Bismarck, a Prussian Prince and one of the great leaders of the 19th century, might have had a more direct line of communication with the powers that be than I do.

The year that homework will pay off

The debt ceiling drama-that-wasn’t is squarely behind us. An eleventh-hour deal was signed, averting the wanton default of the biggest economy in the world, and the global risk-free asset, the US Dollar, marking the 79th straight time that the debt ceiling was successfully raised.

All quiet on the Western Front. Perhaps too quiet.

It was an undeniably good week for markets. US equities rose, breaking their ceiling, which held from September. This was down to two simple reasons: The closing in of a debt ceiling deal and a perhaps slightly more dovish Fed.

Monthly Market Update: Investing money at a time of volatility

Our key theme since the beginning of the year is that the world is a volatile and unpredictable place. To be fair, this could have been our theme every year since 2006 and we would have still hit the mark. But this is not garden-variety volatility.

Quarterly UK Outlook: Q2 2023

The global economy remains unbalanced as the pandemic disrupts global trade, supply chains and international relations. As a result, individual economies diverge and data is unpredictable and volatile.

Monthly Market Update: Volatility and hope

If investors collectively believe in the second coming of QE, then at some point, we should expect a severe market retrenchment. But what if markets are more sanguine than that? What will be the major catalyst, to unleash market forces for risk assets to escape their narrow bands?

Quarterly Investment Newsletter: Winter 2022

The last quarter of the year saw some relief for investors who had been hit from all sides throughout 2022 as markets rallied on the belief that the economy was perhaps showing enough signs of stress to persuade central banks to consider slowing, and then stopping interest rate rises.

Opportunities need swift entry and a lot of patience

Outlooks, our own included, paint quite a grim economic picture at the start of the year. Inflation is really an independent variable and, even if the rate of price rises moderates, prices themselves are set to remain high. Meanwhile, central banks are determined to put the brakes on economic growth in a bid to prevent inflation from becoming entrenched.

A positive message for 2023: The world is rebooting, and that’s good

It is an uncomfortable message that we end the year with, yet a necessary one. Stability should never be seen as the ‘normal’ state of things. And that’s well and truly better for truly long-term investors.

Monthly Market Update: A pandemic that changed the world

Even if we recognise that the world has profoundly changed, we try to analyse it with the eyes of the past. Instead of trying to forecast with the past’s eyes, we need to acknowledge how the present has changed, and develop the right tools to analyse the future properly.

The Outlook 2023: The world we have

Outlooks. The time-honoured financial industry tradition of toiling to write 30-40 pages of annual forecasts promptly binned by April- at the very latest. Yet, the industry gods demand it and deliver we must.

Difficult decisions and difficult truths

It’s bad news for our ‘pivoting’ camp, a word that in the past few months has been grossly and infuriatingly overused. Not only is the Fed speeding up the rate of Quantitative Tightening, but it is also showing no signs that it is ready to change its aggressive tightening policy.

Quarterly Investment Newsletter: Autumn 2022

The third quarter of the year saw markets start to second guess central banks’ resolve to raise interest rates in order to combat inflation. Expectations of a change in monetary policy gathered momentum and caused a rally in global equities of over +11% in a five week period. Alas this proved to be a short- lived bear market rally as central banks, led by the US Federal Reserve, signalled their determination to stay the course with rate rises.

Quarterly Investment Outlook: Paradigm Shift

We find ourselves in the midst of a once-in-a-decade paradigm shift for financial markets and the global economy. The first six months of the year have seen the worst equity performance in nearly a century. Already, average portfolio performance is the worst in twenty years, on par with the 2008 global financial crisis.

Quarterly Investment Newsletter: Summer 2022

Having been absent for decades, the return of inflation is forcing market analysts to learn how to respond to rising interest rates and squeezes on the real purchasing power of consumers’ disposable income. As interest rates rise, the notion of ‘There Is No Alternative’ is diluted, and the prospects for a slowing economy increase, leaving valuations on risk assets vulnerable despite the recent falls.

Turbulent waters may signal a wave of defaults on the horizon

On the 23rd March 2020, the United Kingdom entered its first official lockdown in an attempt to limit the spread of the COVID-19 virus. The initial uncertainty was catastrophic for the economy and many UK businesses were forced to cease trading as revenues plummeted to zero almost overnight.

Quarterly Investment Outlook: Is Globalisation Going in Reverse?

Globalisation is not inherently “good” or “bad”. It is the natural historic evolution of the nation-state, made possible by the internet and the potency of capitalism. But is it over?

Is China facing an economic slowdown?

China was the first country to successfully emerge from the initial Covid-19 wave. People were back to the office in 2020 itself, infection rates plummeted and as a result economic growth was stellar, beating all expectations. China emerged as the winner at a time when most western countries were still coming to terms with the […]

Weekly Market Update: War Drives Market Sentiment

US stocks started the week strongly as reports appeared to show that a ceasefire deal, in which Ukraine would abandon its drive for NATO membership in exchange for security guarantees and potential EU membership, could be possible. However, the mood soured in the middle of the week as Pentagon officials cast doubts on reports that Russia was scaling back operations in Kyiv. Nevertheless, major indices in developed markets ended higher at the end of the week, with the US stock market ending +0.7% higher, the UK stock market rising +0.8%, and European stocks gaining +2.4% in Sterling terms. Emerging markets also fared well, despite China imposing large scale lockdowns on Shanghai and showing weakening manufacturing data, as investors appear to expect that Beijing will take measures to support the economy and financial markets. UK and US bond yields retreated, ending the week at 1.61% (down 8.4 bps) and 2.39% (down 9.8 bps) respectively. Oil fell by -13.9% as Joe Biden ordered the release of 180 million barrels of crude oil from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, ending the week at just under $100 per barrel.

Ukraine risks reignite uncertainty over ECB policy

2012 was a year for the financial history books. Europe’s greatest experiment, the common currency area, was moribund after only twelve years of life. The post-Lehman economic convulsions had driven Greece, its weakest economy, bankrupt, and had brought Italy, its most indebted economy, to its knees. Mario Draghi, then Chair of the ECB, and the […]

Weekly Market Update: Ukraine Tensions Continue to Unnerve Markets

Markets were whipsawed last week as traders scrambled to interpret manage the risk of conflict in Ukraine on top of newly released minutes from the Federal Reserve’s most recent meeting. How have markets reacted? Find out here...

Monthly Market Update: She is tossed in the waves, but does not sink

A hawkish Fed has sent volatility spiking, marking one of the most memorable weeks in forty years. On average, for the past five days the S&P 500’s gap between the day’s highs and the day’s lows hit 3.4%. Since 1982, only 2% of all five-day periods have been more volatile. The most important thing for […]

Inflation momentum will recede. But prices may remain elevated.

There’s a strong possibility we may see the end of the episode soon. But supply chains could take long to mend and overall price levels could remain elevated versus pre-pandemic numbers.

Weekly Market Update: Bonds Fall as Investors Escalate Rate-Hike Expectations

Market Update Equity markets posted overall gains last week after another volatile session. US stocks rose by 0.5% in GBP terms on rising energy prices, and a generally strong earnings season in which 76% of companies beat expectations. Earnings of mega-cap names had a large impact on the wider US equity market, as a 26.4% […]

It’s the worst start in 20 years. Here’s why investors should feel fine.

The worst start to the year inn 20 years leaves investors confused. Here's why we are more relaxed about it.

Weekly Market Update: Global Stocks Fall Sharply As Geopolitical Tensions Mount

Market Update: US stocks fell by -5% last week in their worst 7-day decline since March of 2020, as fears of interest rate rises and increased geopolitical tensions weighed heavily on investor sentiment. Technology stocks in the US were hit particularly hard, falling into correction territory after having reached all time highs several weeks ago. […]

Quarterly Outlook: Sustainomics and a world without QE

2022 is the year where QE (conceivably) ends, and a decade-long Sustainability theme begins. Read our annual outlook.

China’s property sector woes

China’s Evergrande Group has rapidly become Beijing's biggest corporate threat as it wrestles with debts of more than $300 billion as a result of years of aggressive expansion. But that was just the tip of the iceberg.

Well-managed risks in a quickly evolving economic environment

The global economy is entering another difficult phase which features a broad range of emerging and evolving risks. The persistence of the pandemic has disrupted the way business is conducted across the globe, in some ways permanently. The economic impact for developed countries has been somewhat mitigated by emergency fiscal stimulus. However, the debt burdens […]

Investing in a world without QE

Inflation rising may upend a 12-year investment paradigm. Is there life after Quantitative Easing?

COP26 – a recap and what it means for investors

COP26 officially concluded on November 14th, ending two weeks of negotiations. What do the announcements mean for investors?

A Game of Variants: 5 questions answered

The course of the pandemic in 2022 is not expected to be linear. By and large the pandemic continues to determine economic output and supply chain cohesion. An even more transmissible variant, even if completely covered by current vaccines, could materially increase pressures on consumers, businesses and supply chains.

European Canaries Sighing

As the new german government is being installed, European risk indicators are on the rise. Are markets preparing to challenge the Euro's new status quo?

Quarterly Update: Will the Post-Covid Labour Market ever be the same?

'Work' may never be the same after the pandemic. How might things play out? What do businesses need to know to prepare? Read our quarterly economic update

The UK’s energy market and its broader implications

Much of the recent news in the UK has been devoted to the spike in household energy costs and the potential collapse of the number of providers in that market from around 50 to 10 by the end of winter. In fact, since writing this first draft of this piece 2 providers have gone bust, leaving more than 800,000 customers without a provider. Of itself this is an interesting topic: it seems remarkable that rising wholesale gas prices can rupture the UK energy market and reduce the number of energy providers by 80%. For us the more relevant question relates to the wider economy and how energy costs can impact consumer demand and inflation, which contributes to our discussions when deciding asset allocation. This blog post aims to explore the former and explain the Mazars Investment Team thinking on the latter.

Monthly Market Update: Can the Fed be the answer to everything?

For a long time our central theme has been the disconnect between the real and the financial economy. Nowhere has this disconnect been mademore clear than in the Fed’s communication in August. The bullish economic outlook clashed directly with a dovish approach on interest rates.Actions speak louder than words, however, and it is becoming apparent […]

Quarterly Outlook: An investor’s inflation and growth playbook

Investing during the past twelve years has been underpinned by a basic principle: market participants have been encouraged to take risks, mainly to offset the trust shock that came with the 2008 financial crisis (GFC). Each time equity prices have fallen significantly, the Federal Reserve, the world’s de facto central bank, would suggest an increase in money printing, or actually go ahead with it if volatility persisted. Bond prices, meanwhile, kept going up, as central banks and pension funds were all too happy to relieve private investors of their bond holdings even at negative yields. Market risk was all but underwritten.

Quarterly Investment Newsletter: Summer 2021

Developed markets’ continued vaccine rollouts and a corresponding easing of lockdown measures buoyed equity markets during the second quarter despite already starting the period at elevated levels. Global stock markets rose by over +6% in Sterling terms and whilst the US was again the best performing region, European and UK stocks were not far behind. […]

UK stocks are cheap: is this an opportunity or a threat?

Global stocks have rallied hard since the crunch following the Covid-19 outbreak in Europe. However, UK investors noticed that their portfolios were following at a slower pace, even after the UK became the quickest vaccinated country amongst the G7. Since February 2020 the MSCI World, the global equity benchmark, has risen 27% in Sterling while […]

Shariah Investing: the growth of the Islamic Finance gives private clients more options than ever before

This article is the first in a series about Islamic investing Most investment advisers have encountered investors looking for Shariah compliant portfolios at some point. My own experience has previously been one of frustration as the universe of investable funds did not offer enough options to be able to construct portfolios which satisfied clients’ risk […]

The latest position of the ECB

Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, gave a press conference on 10 June following a meeting of the ECB’s governing council. Her speech contained some unequivocally positive observations about the European economy, lamenting a bounce back in services activity, continued strong manufacturing activity and improving consumer spending, all against a backdrop of strong global demand. […]

Is gold a good hedge against inflation?

The problem with gold is that experience does not necessarily support theory. A quick look at the numbers suggests that although gold is widely perceived as an inflation hedge, reality suggests otherwise.

Weekly Market Update: Markets Provide Contrasting Inflation Signals

Market Update It was a steadily positive week for equity markets last week, with all major regions gaining in Sterling terms. Emerging markets equities were the strongest performing, up +1.8%, while Yen strength saw Japanese equities returning +1.2%. Energy was the strongest performing sector globally, as oil prices reached their highest level in two years. […]

Royal Dutch asked to come out of its environmental Shell

Yesterday was a big day for the oil and gas sector as one of its biggest players, Royal Dutch Shell, received the verdict on a landmark hearing to speed up its cuts to greenhouse gas emissions. In the world of responsible investments, this was a historic development. A panel of judges in a lower court […]

Deliveroo’s IPO: The Key ESG Takeaways

Upon floating onto AIM on 31st March, Deliveroo saw more than £2bn wiped off its £7.6bn valuation, after its share price tumbled by more than 26% during its first day of trading. Deliveroo’s heavily touted IPO and its subsequent flop has highlighted the risks of overlooking the ‘S’ in ESG when making investment decisions. Continue reading to know more about the key ESG takeaways from Deliveroo's IPO:

Quarterly Outlook: Inflation: What is it good for?

Inflation expectations rising scared lethargic bond markets and became the most contentious subject of debate in the first three months of the year. Read our outlook to find our position on inflation and the impact on risk assets

Will the rotation into value continue?

While it remains to be seen how long value leadership will last, many of the drivers that led investors to flock to growth stocks have reversed and now favour value stocks.

What is the difference between a Mazars CIO and a boiling frog?

As an analyst I hate metaphors. While they are a very useful tool to turn my thorough -but often thoroughly boring- analyses into actual readable pieces, they also almost always convey a false sense of proportion. One of the most successful, yet dangerously misleading narratives I’ve read lately is one that equates investors to slowly […]

From trade wars to tech wars?

Banning the President of the United States from Twitter might have come as a relief for some, but not for Jack Dorsey, the founder and CEO of Twitter itself. In a series of posts he acknowledged that the move has opened a particular can of worms he was previously keen on keeping shut. The discussion […]

Investment Team Christmas Reading List 2020

As we enter the final weeks of the year the Investment Team has once again come together to compile a list of books suitable for stocking fillers or long evenings spent avoiding Zoom calls with extended family. It has been a challenging year for all, the team have chosen a few books that have helped […]

China’s Fifth Plenum: A Bridge Over Troubled Water?

During their youth, everyone is asked the much-dreaded question – ‘where do you see yourself in five years?’ or ‘what’s your five-year plan?’ the answer to which is never easy. Though, the answer certainly helps to determine how serious the person is about their future and the direction in which they’re headed. A couple of […]

US election update: Two lessons for investors

The election is almost, but not, over and there are significant lessons for investors.

Another Covid meltdown. What investors should know

For the first time since March, the Coronavirus narrative is truly gripping markets.

Quarterly Investment Outlook Q3 2020: Covid Recovery and Anxiety

A quarterly report is not normally a difficult document to put together. Usually it consists of an account of the trending state of affairs, the more possible outcomes and risks to those outcomes. In the past few years, these reports were actually made easier. The US Federal Reserve was underwriting risk at such an unprecedented scale, nearly unwavering for more than a decade, in a manner which suppressed all major hazards to the economy and financial markets. Ever since 2010 the question, repeatedly, had been: “With opportunity costs driven down so much for so long, whatever can bring markets down?”

Three Burning Questions for Investors

In the past few weeks, we have been experiencing a flurry of better-than-expected economic data, especially in the US, while global equities remained near the recent high levels they have been trading at for almost a month. A casual read of the situation could be that the markets had run ahead of themselves, and as […]

Why it pays to be a long term investor

Please read the full article here: In the current investment climate where central bank activity and algorithmic trading strategies are two primary driving forces of asset prices, enabling rapid losses and even faster gains as momentum funds then push winners higher and losers lower, we are reminded how important it is to follow a long […]

Is market optimism justified?

I struggle with the idea how news that nothing has changed in my chances of survival from a killer disease that was enough to lock the whole world down, is enough to send the world’s biggest companies trading at eye-watering 22.6x earnings (the average is around 15-16). It seems to me more credible that the market is running on excessive amounts of QE

Dodging The Depression: The Ace in the Hole

If capitalism is about efficiently allocating resources, credit is the delivery mechanism.

The Great Lockdown – In Perspective

what goals cannot be achieved within the former, might be achieved by investing in stocks and bonds, whose growth is concomitant with the survival of capitalism.

Investing, “in the time of Cholera”

We can comfortably use a phrase that, under other circumstances, would surely risk bringing upon us financial anathema: “This time is different”.

Microsoft Teams User Guide

Please access the user guide for Microsoft Teams here . User Guide – MS Teams All Mazars staff are currently working remotely due to social distancing. Given the importance of face to face contact we are now implementing face to face meetings virtually through Microsoft Teams. Please use this guide to assist you in using […]

Coronavirus: What markets really want to hear

This is a difficult note to write. Investors, stakeholders and human beings in general will always crave comfort in a world that is becoming increasingly uncomfortable. Whether it’s good news or bad news, the certainty of something is better than the uncertainty of, well, everything. Unfortunately, right out of the gate we should say that […]

When the black swan visits

Since 2018, a key concern of financial markets has been the increasing trade tensions between the United States and China, more commonly referred to as the ‘trade war’. With delays and failed negotiations lasting over a year, markets finally breathed a sigh of relief on the 15th of January, as the US President Donald Trump […]

Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer who? More important than you may think

Henry Kissinger famously said “If I want to speak to Europe who do I call?”. That question has never really been answered, and although it could be argued for a long time that person was Angela Merkel, it is now not her immediate successor Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer since she announced she would not be seeking reelection […]

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier… Huawei?

This is a multi-level chess game, touching politics, intelligence and trade, and a move in each field directly affects the other two.

Growing trade tensions

The recent announcement that Huawei will take a “limited” role in the UK’s 5G network has highlighted the growing tensions between different trading blocs, while the temporary truce between Macron and Trump on digital tax, which Trump argues disproportionally affects US firms such as Google and Facebook, gives rise to the chance of renewed conflict […]

Investment Team Holiday Reading List

With Christmas Day just around the corner the Investment Team have compiled a business/economics themed reading list for those looking for a quick stocking filler. Below is a book recommendation from each of us, and a few sentences explaining why you should rush out to your local bookshop, or if it is too cold out, add […]

Boris Unbound

Last night the British public decided to break the parliamentary deadlock which has lasted for over a year and give Boris Johnson a resounding mandate, with nearly 44% of the vote and a comfortable majority after gaining 365 of 650 seats. On the news the Pound surged, as some uncertainty has been removed – markets […]

The Election Paradox

The election tomorrow is somewhat of a paradox. On the one hand, it has been dubbed “The most important election in decades”, one that can “shape the next generation”. On the other hand, however, it offers little visibility when it comes to UK portfolios. Strange as it may seem, both statements might hold true. Throughout […]

Weekly Market Update: Stock gains muted despite signs of a trade deal

Global equities were positive last week, however energy stocks fell precipitously on plummeting oil prices, so that overall in local terms returns were +0.8%. Positive sentiment was boosted as the off-again, on-again negotiations between the US and China appear to be on-again, while a revised estimate of Q3 GDP showed the US economy expanded at […]

Monthly Market Update: New Equity Highs as Economies Tread Water

Markets welcomed signs of an easing in geopolitical tensions in October, with risk assets generally outperforming traditional safe havens. The US and Chinese authorities moved closer to agreeing a partial deal on trade, while the UK once again edged back from the precipice of a no-deal Brexit. Global central banks reiterated their dovish stances and […]

Weekly Market Update: Global Equities Rise, but Sterling Rallies More

Market Update Global stocks rose +0.7% in local currency terms, which translated into a -0.4% fall in Sterling terms. Returns were mixed in local terms, however were universally down in Sterling term as the currency rose +1.0% vs the US Dollar to just short of the $1.30 mark. Emerging Markets had a challenging week falling […]

iPhone-as-a-service? Enter the period of everything-as-a-service

Charles Darwin gave us the theory of evolution. The species most adept to change survives. This model applies not just to organisms but to economies and businesses. In fact, so ubiquitous is the analogy between business and hunting and survival dynamics the language we use to describe ordinary business processes and transactions often stem from […]

The Trillion Dollar Question – Can We Lose Faith in Central Banks

Trillion Dollar Question – Can We Lose Faith in Central Banks However, we would only be touching the surface, inadvertently veering into the sphere of gossip, were we to dismiss such disagreements as mere power plays. In fact, we do not think that investors should care much about ‘who controls the ECB’. Stereotyping, where northern […]

Weekly Market Update: Bond yields rise, Pound rallies on potential Brexit “pathway”

Read our full Market Update Week 40 Global stocks gained throughout the week in local terms, however they fell in Sterling terms after the Pound rallied on news of a potential “pathway” to a Brexit deal. Global stocks fell -1.5% in Sterling terms, with the decline led by weak performance from US and Japanese equities; […]

The World in 2024

Recently, we were asked by our management committee to answer a deceptively simple question: what will the world look like in 2024 from an economic perspective? The task was daunting: articulating a cohesive world view, years ahead. To do that, we need to step back and look at the world we created at the dawn […]

Is there a bond bubble?

Despite a recent selloff, $17tr in global bonds continue to trade with a negative yield. The spread between the US 10 Year Treasury rate and the Fed Funds Rate is negative and at the lowest level since the 2008 crisis. Germany may be paid to borrow for 30 years and the 10 year Bund is […]

Recessions. Remember them?

Recent conversations with our clients have often begun with them expressing concern about the possible effects of Brexit on investment portfolios. Given the lack of clarity on how the situation will unfold or what the impacts might be, this is perfectly understandable. But, whilst the near term prospects for the UK economy are undeniably intertwined […]

Why are investors paying to lend to governments?

It seems we should all be taking on debt. After all, about 30% of the global tradeable universe of bonds is negatively yielding, amounting to around $16.7trn. With bonds that are negatively yielding, holding to maturity guarantees a loss, at least in nominal terms. In other words, it seems you are being paid to borrow. […]

The Current (Trade) War

In the past weeks we saw markets react negatively to fresh tariffs on China. However, it is more likely that traders were simply responding to the Federal Reserve’s attempts to maintain its independence against the US President by taking a more staunch view on the cost of money. The Fed’s independence might just be an […]

Are UK risk assets pricing in the possibility of political realignment?

UK assets continue to trade at a discount to the rest of the world, however, with so much political uncertainty facing the UK this may be justified. Boris Johnson’s new special adviser Dominic Cummings is by all means unorthodox. Mr. Cummings was the Campaign Director for Vote Leave in 2016, and used machine learning and data […]

Market Volatility: This dance we have danced before (and shall again)

Financial market turmoil continues for the second straight week, plunging the S&P 500 close up to 7% from its peak, in a bout of volatility similar to last December’s. The reasons behind the recent tumult are rather straightforward: 1) A stock re-rating, after Fed Chair Powell last week suggested that the central bank is not entering […]

Who will be the leaders of Artificial Intelligence? How should “big tech” be regulated

We are at an inflection point. Technological innovation drives our economy, and ultimately, our standard of living. From rail roads to the Internet, technological progress has pushed our productivity levels to new heights, and we are now on the brink of the next step of this evolution. Artificial Intelligence. Once just the topic of sci-fi […]

Risks are climbing, so let’s buy…stocks?

Check out our new article on recession risk and thoughts on asset allocation: Is it time again for another crash? The US economy, the engine of global growth, has been expanding for 121 months, a historical record. As investors peer into the future, a case of acrophobia (fear of the extremes) is taking hold. “We […]

Disparate Emerging Market Returns

The chart below shows the range of returns across top nine countries in the MSCI Emerging Markets index by market capitalisation. Combined they make up 88.6% of the indexas of the end of March. The vast majority of emerging market equity funds use this as their benchmark. The largest constituent in the EM index is […]

Central Bank Spotlight

In the past few decades, one of the policy decisions that were key for investors was central bank independence. In the past, central banks constituted the arm of the Treasury. Run by top notch economists, their ability to review economic conditions independently has given them the power to reduce economic volatility by making sure that […]

The real Champions League winners

Football clubs fall into the ‘Consumer Discretionary’ category of businesses. I’m not entirely sure I would want to tell a Cardiff City fan that their support is discretionary. Regardless, football clubs are a fairly niche investment, with business models significantly different from a regular business. After all they have two measures of success which don’t […]

Could rising oil prices reverse slipping inflation?

Do you have a significant amount of financial assets (bonds, equities) or a significant amount of financial liabilities (loans and mortgages outstanding)? In all likelihood you have a combination of both, which makes the following simple statement moot: people with savings dislike inflation, while those owing money tend to benefit from it. Essentially the real […]

The return of loss making IPOs

Is this a bubble or a source of returns for diversified investors? What is the “Uber bet”? We live in a low interest rate super-liquid world, with a lot of money chasing too few opportunities. Overall equity issuance has stagnated over the last few years as CEO’s use buybacks to please existing shareholders, removing equities […]

Fear the stimulus more than the trade wars

It feels that Donald Trump’s “trade wars” with China have come to dominate financial headlines as they were considered the main culprit for last week’s stock market correction. However, a closer look indicates that the whole issue is, at this point, essentially noise, both in terms of market indices and the economy. First of all, […]

How populism will end: A Game of Thrones Approach

Game of Thrones is finally ending, with some great lessons about human excesses. After almost 75 hours of watching the world’s most successful show, plus another 20 reading the books, I now find myself not too keen on watching the final episode. I feel that there’s no walking back on the damage done from showrunners […]

Are UK investors ready to pay for 2016’s ‘free lunch’?

In 2016 investors in global equities experienced a fretful start to the year as concerns about a possible Chinese hard landing caused a fall of over 10% in the first quarter of the year. As has been the pattern over the last few years these concerns quickly subsided in the face of continuing ultra-loose monetary […]

China Doll: Our Q2 Economic Outlook

As the world slows down, it looks to China as both a cause and a solution. Will the world’s second largest economy come through? Read our MFP Quarterly Investment Outlook Q2

Game of Thrones S8: A Zombie Primer In Portfolio Risk Management

“Game of Thrones” is back on the screen, for the 8th and last season. Proselytised fans around the world are flocking to learn the final fate of Cercei, Daeneris, Jon Snow, the Stark children and Tyrion Lannister in what has become the most popular series of all time. The final season starts where the previous […]

Will China Keel Over in 2019?

The key question in 2019 is not Donald Trump or the trade wars between the US and China. The real Gordian knot is China itself. The world’s second largest economy is going through a painful transition, weaning off its dependence on manufacturing and exports and focusing on improving the standard of living for its citizens, […]

Nike: weak sneaker, weaker brand?

Last week NBA star Zion Williamson’s sneaker tore into pieces early on in his game vs UNC and he subsequently left the court with a knee injury. Zion is widely regarded to be one of the most promising young stars (He is just 18 and is projected to be the first overall pick in the […]

Can China’s policy makers really prevent the slowdown?

Over the past few months, ‘trade-wars’ have moved from obscure historic reference into everyday jargon, casually dropped by consumers on sentiment surveys. The US, suffering from chronic trade deficits and increasing imbalances in its co-dependent relationship with China, has set its sights on trying to disrupt this process, a policy that has had an impact […]

How long can Italy withstand the chains of the Euro?

A populist Eurosceptic government, paired with a budget deficit target below 2% and membership of a monetary union is putting a lot of pressure on the Italian economy. The inflated currency strength due to strong countries like Germany sharing the Euro and the inability to use independent monetary policy has cornered Italy into a tough […]

How do you guarantee debt using debt, and so make that debt cheaper?

It sounds like a story from the heady days leading up to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and something that will end in disaster. Rating agencies assigning the highest possible rating to an auto maker’s debt which is ‘guaranteed’ on clients paying for leases of its cars (which is essentially debt), with repayment on the […]

Weekly Market Update: BoE keeps rates on hold

Read our full Market Update Week 6 Market Update It was a mixed week for equities, with US stocks ending the week up +1.3%, despite President Trump ruling out a meeting with President Xi before March 1 to strike a trade deal and put trade concerns to rest. It was also a positive week for UK […]

Theresa May’s 157 Brexits – and beyond

The Economist magazine has characterised Brexit “The mother of all messes”. To exit a trade agreement so comprehensive that over the past half century has come to encompass virtually all aspects of the British economy is, by and large, unprecedented. To do so in less than three years, in the midst of political turmoil, is […]

Mazars Quarterly Investment Outlook: 2019 Outlook

Read our full Mazars Quarterly Investment Outlook- Q1 2019 Outlook 2019 Sometimes it appears that the world is getting louder. The Norwegian Sociologist, John Galtung said that if a newspaper came out once every 50 years, it would not report half a century of celebrity gossip and political scandals but rather momentous global changes such […]

Monthly Market Update – December 2018

Read our full Monthly Market Update December 2018 November data indicated that the global economy continues to slow, despite a pick up in the services sector, as trade conditions deteriorate. Risk asset divergence, a theme of the previous quarter, seems to have abated, as US risk asset underperformance closed part of the gap with Europe and […]

Will Donald Trump be happier with the 2019 Fed?

Having regularly declared that he will only hire the best people, Donald Trump has been rather vocal in decrying the actions the Federal Reserve has taken since Jay Powell, his choice for Fed Chair, took office. Mind you he has decried many of his appointees at one point or another, with his Attorney General Jeff […]

Italy’s Greek Moment?

The European commission confirmed that it would be starting the excessive deficit procedure for Italy. Under Eurozone rules, no country is allowed a deficit higher than 3% of its GDP, but the Italian budget proposal challenged the EU directly by assuming significantly higher growth rates. According to Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis “The Commission confirms […]

Weekly Market Update: Global stocks continue their rebound while Oil prices drop further and Brexit uncertainty heightens

Read our full Market Update Week 46 Market Update Global stocks continued their rebound this week, with both Global and European equities up +0.3%. Emerging Market equities led the pack, returning +2.5% as the slide in oil prices gave a boost to emerging market currencies. UK Stocks were hit by further Brexit volatility, hardest hit stocks […]

Brexit Update: What now?

New Update! Monday 19 November 2018 After Friday’s dramatic cabinet session, which saw a third Brexit Secretary, Dominic Raab and Work & Pensions Secretary Esther McVeigh resign, there are several possible options on the table: 1) The deal might still go through parliament. Although divisions in the conservative party are high and it is unlikely that other […]

US Midterm Elections: What is the outlook for markets?

The US goes to the polls today for midterm elections. Every seat of the lower chamber (the House) is up for election (as it is every two years!), while a third of the upper chamber (the Senate) will also be voted on (Senators are elected every six years). For comparison to the UK Parliament, the […]

Angela’s long goodbye and what it means for investors

When Angela Dorothea Merkel became president of her party, the CDU, in 2000, her sights were set on the highest echelons of leadership in Germany. In 2005, she followed Helmut Kohl, her mentor, and Gerhard Schroder by becoming the third post-war leader of a united Germany. Furthermore, she was the the first who grew up […]

Weekly Market Update: Global stocks down for the week, capital flows to US bonds, UK budget contingent on Brexit

Read our full Market Upate Week 43 Market Update Global stocks continued to slide this week, with US stocks leading indices lower, the S&P 500 falling -2.2% in Sterling terms. The NASDAQ lost -3% due to disappointing results from Tech companies and a drop in the Consumer Discretionary sector following a disappointing sales outlook from […]

Mazars Quarterly Investment Outlook: Whatever Happened to the Global Synchronised Cycle?

Read our full Mazars Quarterly Investment Outlook – Q4 2018 Global Divergence In an early 2010 report Morgan Stanley warned that the biggest consequence of the 2008 global financial crisis could be isolationism and the reversal of a 50 year old trend which saw increasingly open borders, open trade and freedom of movement. As each […]

Mazars Wealth Management Investment Newsletter October 2018

Read our full MWM Newsletter October 2018 The global economy continued to grow in the third quarter of 2018 despite a backdrop of concerns over the continued imposition of trade tariffs primarily by the United States. It is apparent that any optimism a compromise between the US and its trading partners (China in particular) can […]

Monthly Market Update – October 2018

Read our full Monthly Market Update October 2018 September data continued to indicate global economic and risk asset divergence, consistent with a mature economic cycle, with USD assets rising as a result of Mr. Trump’s policies. The global economy is also diverging, with the US on a faster expansion path, while Europe and EM are […]

Weekly Market Update: Stocks sell off globally on rising bond yields

Read our full Market Update Week 41 Market Update Global indices suffered significant falls last week, down -4.1% in local terms and -4.5% in Sterling terms. US equities led the weak performance, experiencing their biggest losses in 8 months on Wednesday. Technology stocks were particularly affected as market participants reacted badly to rising bond yields. […]

Weekly Market Update: Fed hikes rates as oil hits year highs

Read our Full Market Update Week 39 Market Update US stocks dropped -0.2% in Sterling terms last week, as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 0.25%, with investors concerned about the elimination of the word “accommodative” from the Fed’s policy statement. UK stocks were up +0.3% and UK 10 Year Gilts were up +2.0 […]

Monthly Market Update: EM’s Dollar Turmoil

Read our full Blueprint Sept 2018 August data continued to indicate global economic and risk asset divergence, consistent with a mature economic cycle, with USD assets rising as a result of Mr. Trump’s policies. The global economy is also diverging, with the US on a faster expansion path, while Europe and EM are slowing down. […]

Weekly Market Update: Bank of England and ECB keep rates unchanged

Read our full Market Update Week 37 Market Update Equities rose across the board last week, both in local and Sterling terms. UK stocks gained +0.4% with US and Global stocks up +0.1% and +0.3% in GBP terms. Other areas fared even better, as European and Japanese equities rose +0.8% and +0.6% respectively. However, Emerging […]

How British retailers “gamed” themselves into a corner

When my daughter was first born she had trouble sleeping and hated her cradle. So I used to hold her by to the kitchen fan (new parents take note, this works!) for about 10’, until she was fast asleep. It worked magic every time. Until it didn’t. A few weeks later she didn’t like it […]

The Fall of the High Street

Established in Glasgow in 1849 under the name of Arthur and Fraser, House of Fraser (HoF) is a household name across the UK. The British department store group has 56 stores and 2 outlets across the United Kingdom and Ireland. However, despite its long history, strong brand, and rich heritage, HoF has become the latest […]

Fork in the Road for Tesla

There has been a lot of coverage of Elon Musk’s musings as to whether he will take Tesla private again, having publically listed the company in 2010. Having shares listed in a company is supposed to bring benefits of increasing the ease of raising capital, while the greater liquidity and heightened corporate governance needed to […]

Why look beyond the US for equity returns?

The US stock market has made some impressive gains year-to-date. In January the S&P 500 reached a record high of 2872.87, with the exchange falling just 10 points short of this figure two weeks ago. Apple also recently made headlines worldwide when it became the first US company to be valued at a staggering $1tn. […]

European Risks Primer: Richlandia and Poorlandia

The article was originally published in the Money Observer on the 20th July 2018 The potential breakup of the Euro has been a permanently armed grenade under the bed of the global economy for almost two decades. The recent Italian elections driving yields up and the Euro down reminded allocators that European risks have never […]

Unconventional monetary policy increased house prices. Will its withdrawal spark a sell-off?

In March the Bank of England released a working paper titled ‘The distributional impact of monetary policy easing in the UK between 2008 and 2014’. For context, quantitative easing and ultra-low interest rates have been blamed by many commentators for a rise in inequality which has fermented populism in recent years. However the paper found […]

Mazars Quarterly Investment Outlook: Mind The Liquidity

Read our full Mazars Quarterly Investment Outlook-Mind the liquidity A cautionary tale There’s an old story about a man who was marooned on a deserted island. Searching for food and water, he instead found a cave hiding a chest of pirate treasure. No water in sight though. He spent his last few days, next to […]

Monthly Market Update: Markets unable to break out

Read our full Monthly Blueprint July 2018 Month In Review On the face of it, June has not been an exciting month for risk assets. Developed market stocks ended the month roughly in the same place as they started it, while long bond yields were little changed. However, beginning and end figures mask not only […]

Weekly Market Update: BoE’s Chief Economist dissents to put 2018 rate hike on table

Read our full Market Update Week 25 Market Update Global stocks turned negative last week following two weeks of positive performance. Emerging Market equities were the worst hit, falling -2.0% in Sterling terms, as rising trade war fears also weighed on global equities, which were down -0.7%. Japan was also badly hit due to its […]

The difference between a skirmish and a (trade) war

Why geopolitics now matter more In the past few years, investors and economies have grown somewhat insensitive to geopolitical surprises. Brexit, for example, did not cause the massive initial shock to either the economy or the stock markets that many analysts had predicted. Neither did Mr. Trump, whose election has sent stocks soaring by more […]

How much of the FTSE’s strength is due to currency effects?

Currencies have historically been extremely volatile, and predicting FX movements is recognised as a very difficult and risky strategy. Exchange rates move on several, often unpredictable, macro-economic factors, including differences in interest rates or inflation, geopolitics or due to government intervention such as capital controls. Many funds have exposure to currency risk from investing in […]

Combustible Commodities, Bruised Banks: Why Brexit isn’t the only headwind for UK equities

Whisper it very quietly, lest we jinx it: UK equities have been on a strong run recently. When was the last time you could say that? Certainly not since Brexit, which has been blamed for the poor performance versus global peers. However looking at the 4 quarters leading up to and including the Brexit vote, […]

Following recent elections, could Italy give the Euro the boot?

Last year Europe was the darling of equity investors, as strong growth and improving sentiment throughout the Eurozone meant that it was only behind Emerging Markets in Sterling terms, which had a stellar year in spite of concerns about Trump, over the course of 2017. However, like Emerging Markets, Europe has had a relatively poor […]

Trading Trump

This week I was asked to write 180 words on whether President Trump was a ‘welcome disruptor or market menace’ and how his policies can be factored into investment decisions. Despite becoming tired of the circus surrounding the 45th President of the United States, the question poses an interesting debate. Donald the Disruptor Innovative disruption […]

Mazars Wealth Management Quarterly Investment Outlook Q2 2018: The new “new normal”

Read our full MWM Quarterly Investment Outlook Q2 2018 The first quarter of 2018 saw a return of market volatility and a reversal of gains from the end of 2017. Despite a strong January, global equities finished the quarter down 2.1% in local currency terms, but 4.7% for UK investors as the Pound continue to […]

Macro of the Week – UK GDP sees marginal improvement

The NIESR GDP growth estimate for the 3 months to March was revised up to 0.2% from 0.1% in February, having been revised down from 0.3%. However the figure is still a reduction from the 0.4% growth seen in Q4 2017. Quarterly growth of 0.2% equates to just 0.8% annual growth. According to Amit Kara, […]

Gender pay and the changing face of the workforce

The gender pay gap is a hot topic in offices across the country as the April deadline for companies to report their pay gap has recently passed. The gender pay gap helps to highlight major demographic changes, in terms of the age and gender, affecting the UK’s labour force. The gender pay gap In an […]

Macro of the Week – John Williams takes over NY Fed

In a move that was expected, John Williams will move from the San Francisco Fed president post to take the same position at the New York Fed. He takes over from William Dudley, who late last year announced he would be leaving by mid-2018. The role comes with vice-chairpersonship of the FOMC – the Fed’s […]

Macro of the Week – US confidence indicators soaring

The recent tumult in equity markets arrived despite robust macroeconomic data in the US, for example the latest earnings season saw 73% of companies beating expectations for earnings. Recent data for consumers and businesses appears to support this view. The NFIB Small Business Optimism index for February rose to 107.6 from 106.9 – the highest […]

Weekly Market Overview – Trade war concerns weigh on markets

Both US equities and the US Dollar fell last week when multinational companies such as Boeing were hit as Donald Trump sought to impose new tariffs on China, pressing China to cut its trade surplus with the US by $10bn. As a result, there is an increased likelihood of a trade war between the worlds […]

Are higher interest rates a necessary evil?

“An economist is an expert who will know tomorrow why the things he predicted yesterday didn’t happen today.” Laurence J. Peter When I was studying economics at university (not that long ago) I was taught under ‘neo-classical’ thinking, which had come to pre-eminence in response to the period of ‘stagflation’ in the 1970s. Under stagflation […]

Macro of the Week – US nonfarm payrolls strong

In a reversal of the recent trend where good data is bad news for stocks, and bad data is good news, US equities rallied on Friday after the latest nonfarm payrolls report. The report showed the highest job creation […]

Tariffs: What could Trump do?

Donald Trump roiled markets on Friday by announcing on Twitter: He has since confirmed that he plans to impose tariffs of 25% on steel imports and 10% on aluminium. The move has been widely met with criticism, not just from Democrats but from many members of the Republican Party, including the House Speaker Paul Ryan. […]

Xi Jinping’s Infinite Rule

Things have been looking up for China recently, as market sentiment towards the world’s second largest economy has finally started to take a positive turn. Since 2015, when the country’s stock market sold-off sharply and the Shanghai Composite Index crashed 45% in under two months, investors have understandably been wary of China. Redemptions in Chinese […]

Macro of the Week – US Q4 GDP revised down

US economic growth slowed slightly more than originally expected in Q4. On Wednesday the Commerce Department released revised quarter-on-quarter growth at an annualised rate of 2.5%, down from 2.6%, although this was in line with economists’ estimates. This compares to an annualised growth rate of 3.2% in Q3. The growth in consumer spending (3.8%, the […]

Weekly Market Overview – Markets fear Taylorisation of Fed and trade wars

Markets continued their recent rocky period, with two separate events causing unease for investors. The first was Jay Powell’s first congressional testimony on Tuesday where he hinted at a faster pace of interest rate rises and stated a preference for rules based interest rate decisions. For example the Taylor Rule proscribes an interest rate for […]

Macro of the Week – UK GDP slowing

The UK economy grew more slowly than previously estimated in Q4 2017, increasing by 0.4% quarter-on-quarter according to the second estimate by the ONS. This figure was a 0.1% downgrade from the original estimate. The downward revision was due to slower […]

Black Swans are not so Black (or rare)

A “Black Swan” is a very popular notion in modern stock market commentary, yet the phrase originates from a time before the public listing of stocks. In 16th century London, people used an old Latin quote : “a rare bird in the lands and very much like a black swan“, based on the presumption that […]

Bargain Basement Britain

Over the last month global equity markets have sold off; since the 15th of January the MSCI AC World Index has fallen -4.12%, the S&P 500 -4.22% and the Japanese Nikkei -6.0%. The UK market similarly has tumbled with the FTSE 100 plummeting -6.36% over the last 4 weeks1. With stocks cheaper compared to a […]

Macroeconomic View – French unemployment down

French ILO unemployment dropped unexpectedly from 9.6% to 8.9%. It was further proof of the strength in the French, and subsequently, the European economy. European equities lost 1.5% briefly after the US inflation report was released, with figures higher than expected. The market recovered, but the move is indicative of the factors that affect traders. […]

Macro of the Week – US rate hike still on the cards

The recent sell-off in markets and spike in volatility has so far been met by a wall of silence from the new Fed Chair Jay Powell. On the day of being sworn in, Powell faced a drop of 1,175 […]

Macroeconomic View – German exports accelerating

German exports were weak for the month, up only 0.3%, but are still accelerating year-on-year. Chinese exports were stable, but imports picked up significantly, offsetting last month’s weak data. UK The Markit Services PMI dropped slightly to 53 from 54.2. The Halifax House Price Index year-on-year for the 3 months to January fell from 2.7% […]

Market Comment – Risk on – Redux

After an unusually quiet two-year period, investors were once again reminded that volatility is part and parcel of the investment process. Global stocks suffered their worst week since 2016 and the sixth worst overall week since the recovery began in 2009. More importantly, bond prices also fell, as did other traditionally safer assets such as […]

Monthly Market Outlook: February 2018

Read our Monthly Market Update Global equity markets were positive again, registering a 5.3% performance in January, benefiting from the positive sentiment and the passing of the US tax reform at the end of 2017. The macroeconomic environment was less supportive, however, as some key indicators suggested that global economic momentum was slowing down in […]

Macro of the Week – US wages accelerate

US hiring picked up in January and wages rose at the fastest pace since the GFC. Hourly earnings increased 0.3%, resulting in an unexpected year-on-year increase of 2.9%, up from 2.7% in December (which was also revised up from 2.5%). This was on the back of a nonfarm payrolls increase of 200k, which was upwardly […]

Macroeconomic View – Market Correction

UK Consumer confidence rose in January from -13 to -9, above expectations for the figure to remain flat. Nationwide housing prices year-on-year for January increased to 3.2% from 2.6%, the highest reading since March last year. The BOE’s concern surrounding borrowing was confirmed as consumer credit figures climbed to £1.52bn in December from £1.5bn the […]

Markets sell-off at fastest pace since 2011

By David Baker, Chief Investment Officer After a strong start of the year for equity markets, global stocks shed almost 5% of their value on Friday and Monday. US equities are now 6.2% below their highs, turning negative for the year, as are global equities (-6.5% from their highs). The S&P 500 is now trading […]

Equity Storm in a (Bond) Teacup

Last week marked a 3.5% pullback for global equity markets, the first since 2016. The move comes after a very good month, January, during which equities rose to fresh highs, gaining 5.2%, prompted by exuberance related to the US tax reform. However, the arrival of February marked fresh concerns for investors. First and foremost, economists […]

Macro of the Week – US GDP disappoints

Provisional readings for US Q4 2017 GDP growth came in at 2.6%, slightly below the 3% figure expected by the market. This is an annualised figure and therefore growth for the quarter was actually only 0.1% behind expectations. Strong imports were the main reason for the surprise to the downside, subtracting 1.1% from the growth. […]

Macroeconomic View – Weak US Dollar

Dollar weakness persisted last week as ambiguous messaging from the US Government confused investors. Headline capital goods orders (blue) were robust, however the core capital goods component (red), the less cyclical of the two, has continued to weaken since September. UK Average earnings increased from 2.3% to 2.4% year-on-year for the 3 months to November, […]

Market Comment – Macro headwinds

Last year was very positive, both in terms of stock market and macroeconomic volatility (the volatility of macroeconomic releases). In recent weeks, however, we have noticed a deterioration in macroeconomic releases, especially in the US. Lower inventories and higher imports took a toll on GDP. More detailed data on capital expenditure also shows weakness in […]

Weekly Market Overview – US Dollar slide sees negative equity returns for UK investors

Global equities were mostly positive in local terms last week, however a fall in the US Dollar, combined with Sterling appreciating, meant that returns for UK investors were generally negative. Weak US Dollar performance was largely due to a statement at Davos by US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin being interpreted as suggesting that the US […]

Macro of the Week – German coalition considerations

German elections in November were met with cautious optimism by markets, with Angela Merkel’s CDU party gaining the most seats and seemingly in position to lead a coalition, so maintaining the status-quo in German politics. However negotiations have proven more difficult. The SDP, which claimed the second most seats, initially planned to be the main […]

Comments