Is gold a good hedge against inflation?

Investors and consumers have spent the past two months inundated with news about resurging inflation. Any investor playbook worth its salt would almost instantaneously overweight gold in times of higher inflation. In theory, this should work. Inflation is supposed to be a consequence of excess money in the economy. People have more to spend, demand is higher and, with supply unchanged, prices go up. The antidote to excessive money is higher rates, which curb lending and restrict money creation. Until the new equilibrium takes place, consumers, the theory says, should rely on a more tangible asset to maintain wealth.

Throughout history, humanity has experimented with many tangible stores of wealth. From livestock and land to more exotic forms of ‘money’ such as knives (Zhou China), dolphin teeth (Solomon Islands), salt (Roman Empire), squirrel pelts (Russia) and seashells (North America). Desperate from the hyper-inflation in the early 1920’s, Germans used actual wooden money called ‘Notgelds’. However, since the Palaeolithic period, c 40,000 BC, 33 millennia before the appearance of the first cities, no asset has been a more reliable store of wealth than gold.

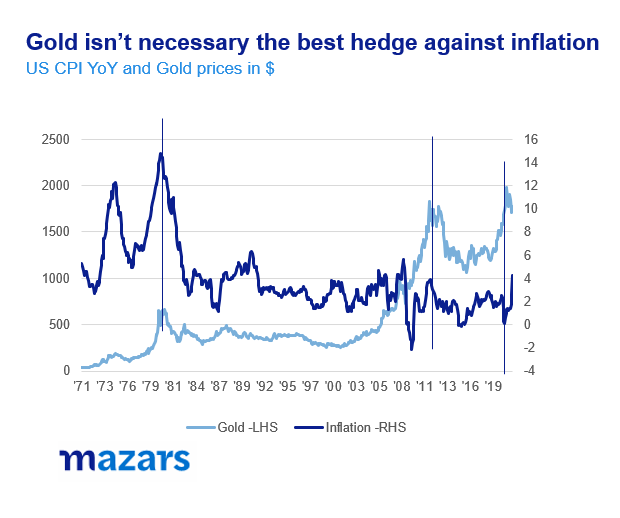

The problem with gold is that experience does not necessarily support theory. A quick look at the numbers suggests that although gold is widely perceived as an inflation hedge, reality suggests otherwise. In quiet inflationary periods gold prices rise and fall as a result of other fundamentals, such as central bank behaviour, investor and consumer demand. Additionally, its historical patterns were unequivocally affected after the introduction of Gold ETFs in the early ‘00s which made it more accessible to everyday investors who can now buy it without having to pay the transaction costs associated with buying gold from central banks or directly from exchanges.

A simple calculation from 1971 suggests a very small positive correlation (13%) between returns of gold and changes in US inflation. From 1986 to 1990, US consumer inflation rose from 1.1% to 6.3%. In the same period, gold lost 4% of its value.

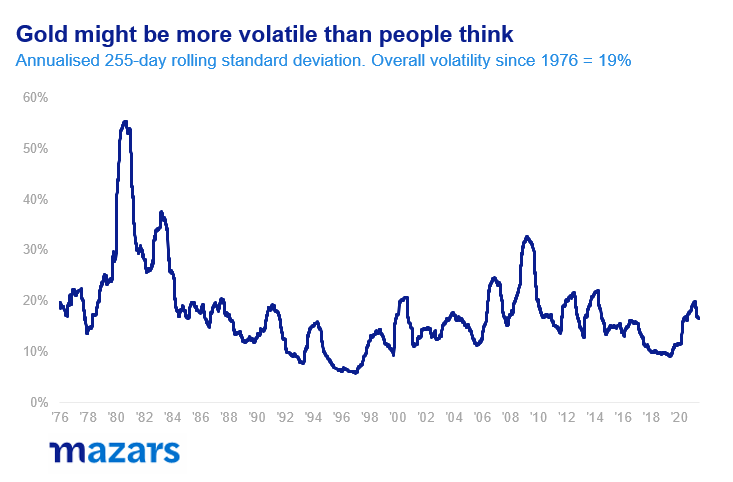

Its volatility may also surprise some investors. Annualised rolling 255-day standard deviation (a common measure of volatility) since 1976 is 19%, above that of equities (13%) and bonds (around 5%-7%).

Having said that, correlations between gold and inflation tend to increase sharply in more acute inflationary episodes, like in 1981 and 2011. Does 2021 qualify as such an episode? We believe so, as numbers suggest the highest inflation figures in a decade with some uncertainty going forward as to whether it will continue.

Investors, however, should be mindful that while correlation increases during the acute phase, it tends to decrease dramatically as inflation decelerates. Currently, central banks are not expecting a long-term bout of inflation. By historical standards this could mean some de-correlation soon.

In terms of inflation, gold can be a good trade if someone predicts inflation in advance. However, buying and holding after the event may not be as successful.

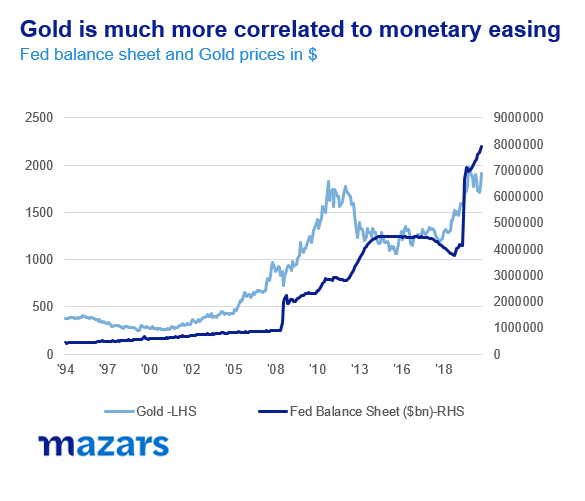

If anything, gold has proven itself to be a more effective hedge against the enormous sums being printed by central banks in reason times. The correlation between gold prices and the size of the Fed’s balance sheet is nearly 87%.

Gold prices involve central bank demand, quirky consumer preferences which different around the globe, speculation and investment heuristics. Instead of trying to time this extremely complex market with many different players, investors should consider gold as part of a wider long-term portfolio, to take advantage of all the reasons other would buy it and to protect some of their assets against unexpected changes in the inflation expectations of others.

Comments