Thought Leadership | 11 December 2019

The election tomorrow

is somewhat of a paradox. On the one hand, it has been dubbed “The most important

election in decades”, one that can “shape the next generation”. On the other

hand, however, it offers little visibility when it comes to UK portfolios.

Strange as it may

seem, both statements might hold true.

Throughout the past

few years, the British electorate has been steadfast in its request that the

status quo should change. The parties have listened and have placed

unconventional leaders at their helms. Both Conservative and Labour leaders can

credibly promise that the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

will be a different place after December 13th.

The next government

will oversee the biggest change in status quo the UK has seen in decades. The

only question, for citizens and investors alike is what does this really mean,

and how it addresses their uncertainties.

A Conservative win

would mean more certainty about the structure of the economy, but uncertainty

over trade with the EU, the country’s largest trading partner. A Labour win

could mean more certainty over Europe (could is the operative word) but less

certainty over the overall economy. The only thing the two parties agree on is

willingness to incur higher deficits to spend money on the economy.

Investments,

especially in real assets, such as factories or homes, tend to be illiquid and

time-binding, which means that a certain degree of forward visibility is

required. If one does not know either what one’s market is, or what the

business climate will be, neither of which will be convincingly answered on the

day after the election whatever the outcome, then one may defer of even cancel

a big spending decision. Predictably, underinvestment has been a significant

headwind for economic growth, especially in the past three years.

Nevertheless, one

might argue, what if investors chose to believe and buy in early on electoral promises,

hoping that either Conservatives will deliver the “Brexit dividend” and achieve

a record-time trade deal with the EU, without compromising the UK’s integrity,

or Labour will successfully demolish income and wealth inequalities that

hamstring real growth and usher in an era of inclusive growth..

Even if that were the

case, it would still leave long term investors in a bind. The UK economy is one

of the most open systems in the world, its trajectory concomitant with the

global economy. The world has been suffering from a slowdown mostly induced by

the traumatic 2008 experience which has reduced demand for investments and

consumption. Coupled with miserable demographics, surging trade tensions,

crushing debt levels and a significant Chinese slowdown, it is no wonder why

our time is often called “secular stagnation”, a pseudonym, for “Japanification”.

Before 2008, the world was growing by 5%. Now, on a good year global growth is

slightly above 3%. Add Brexit and business climate uncertainties into the mix

and one can see how investors may only trust the strongest of investment cases.

Any chink, or even potential chink in the armour is big enough doubt for

portfolios facing a world that has barely been growing for a decade.

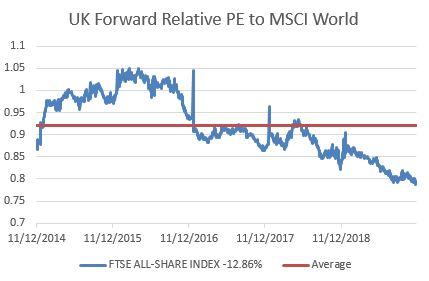

Even if the outcome

of the election was certain, which we feel that due to tactical Remain voting

and shifting electoral demographics (a third of British citizenship

applications now come from EU nationals, as opposed to 12% before the election)

is far from the case, fact remains that UK risk assets lack the forward

visibility which would make them an iron-clad investment case for international

portfolios. We thus feel that investors will stay on the sidelines until a

comprehensive and realistic view of what the UK will look like in 10 years has

emerged. Can this take place in January 2020? Maybe. But chances are the

process, and thus the uncertainty, might be a bit longer than that.

Comments