Thought Leadership | 31 May 2019

Do you have a significant amount of financial assets (bonds, equities) or a significant amount of financial liabilities (loans and mortgages outstanding)? In all likelihood you have a combination of both, which makes the following simple statement moot: people with savings dislike inflation, while those owing money tend to benefit from it. Essentially the real value of savings tends to be eroded by inflation (although certain asset classes offer more protection in this regard). On the other side of the equation imagine if all costs, including wages, doubled overnight – in real terms your fixed mortgage would have halved in value!

Inflation is an incredibly important consideration in wealth management, despite it being a fairly abstract concept, which is why we spend so much time trying to understand it. A theory that is prevalent in the financial press is that we are in a ‘lower for longer’ environment – low growth combined with low inflation. This isn’t ideal as quite obviously a high growth environment lifts living standards. However combined with low inflation it does mean that those living standards aren’t diminished through rising prices.

But are we really in for a long period of low inflation? Is the future going to be dominated by ‘The Amazon Effect’, whereby many of the costs of delivering goods have been removed through automation and direct delivery of goods, driving down prices. Or has the experience of the tepid recovery since the Global Financial Crisis erroneously encouraged commentators to project the low inflation of the period into the future?

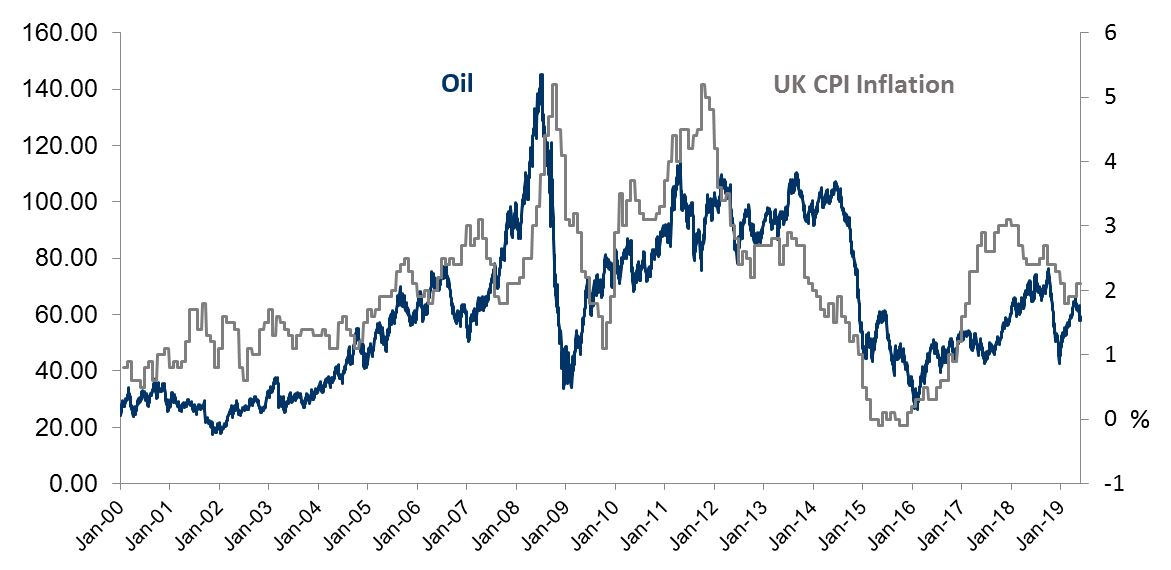

One factor that often appears to be overlooked in the lower for longer arguments is that since 2015, when this theory started taking hold, the price of Oil has been low in comparison to recent history. Since 2000 there has been a clear relationship between inflation and oil prices, although inflation has tended to move with about a six moth lag. Inflation has picked up recently, although that was largely a function of a falling Pound following the Brexit referendum, and has drifted back to the 2% target for the Bank of England.

However there is no guarantee that oil prices will remain subdued, and they are up 28% this year, which sounds like an alarming figure. In fact, having bottomed out at about $27 in January 2016, prices reached as high as $75 in October of last year. There has since been a correction, although prices have again recovered to around $57. This level is still fairly muted by standards of the last 20 years, although over the very long term is above average.

The oil price, and more precisely where it is headed, is something most people in finance will run a mile to avoid having to forecast. The reason are the immense complexities of analysing global supply and demand dynamics. One consistent rule is that major global conflicts, especially in the Middle East, have tended to result in a spike in oil prices. For this reason we are closely monitoring the developments of President Trump’s mounting rhetoric in regards to Iran’s nuclear power programme. Given this potential catalyst and the current low price, it seems there is significant upside potential.

However the likelihood is that for many reasons the days of $100 oil are gone. Whereas in the past supply was largely dominated by OPEC, unconventional producers such as US shale have come to the fore in recent years. Indeed there have been accusations that OPEC, and especially Saudi Arabia, got too comfortable/greedy with high oil prices in the early part of this decade, opening the door for US shale producers. These producers had big start-up costs and were initially only viable when oil costs were high. However the technology has improved significantly, so that shale producers have gone from being marginal producers to a permanent fixture of oil markets, even when Saudi Arabia tried to squeeze prices lower to drive them out of business. These companies aren’t likely to go away any time soon.

And now there is a new player in town: green energy. Energy providers in particular have a strong incentive to switch to renewable forms of electricity generation should the price of traditional fossil fuels rise to an uncompetitive level. Whereas opponents of green energy fear it could drive up energy prices for consumers, recent history shows it is instead more likely to act as a cap. Perhaps low inflation is here to stay.

Comments